Download Download & share this Knowledge card in your network [Free Download]

Introduction

Imagine the comforting weight of a parent’s hand on your shoulder, a gentle hug from a friend, or the soft texture of a favorite blanket. These everyday sensations, often taken for granted, are typically experienced as comforting and reassuring. But for an autistic child, the same touch can trigger an overwhelming wave of discomfort, anxiety, or even pain. A simple pat on the back might feel like a sharp sting, a hug could feel like being trapped, and the feel of certain fabrics might be akin to sandpaper against their skin.

This heightened sensitivity, or hypersensitivity, is a common experience for many autistic individuals. It can manifest in various ways, affecting not just touch, but also other senses. Bright lights might feel blinding, everyday sounds might be deafening, and certain smells could be nauseating. This sensory overload can make navigating the world a challenging and often distressing experience.

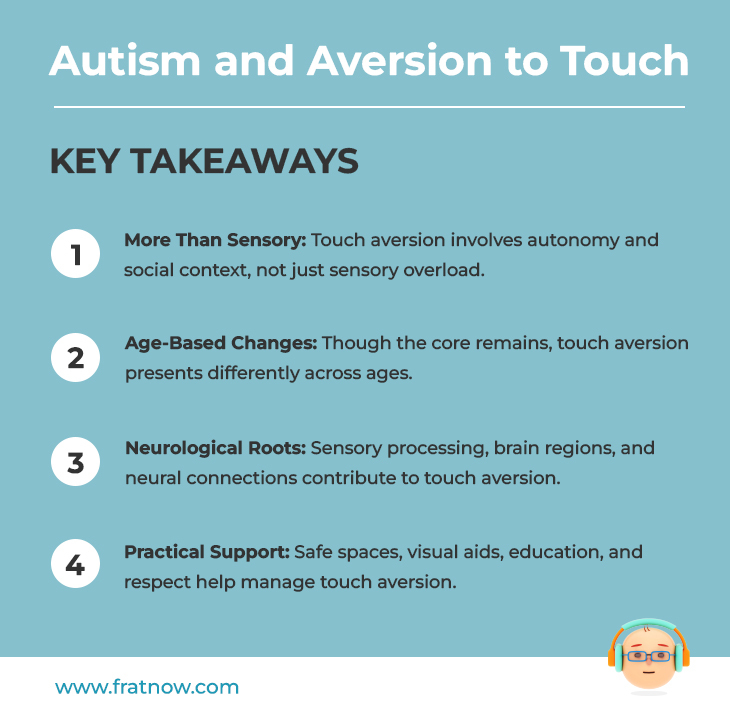

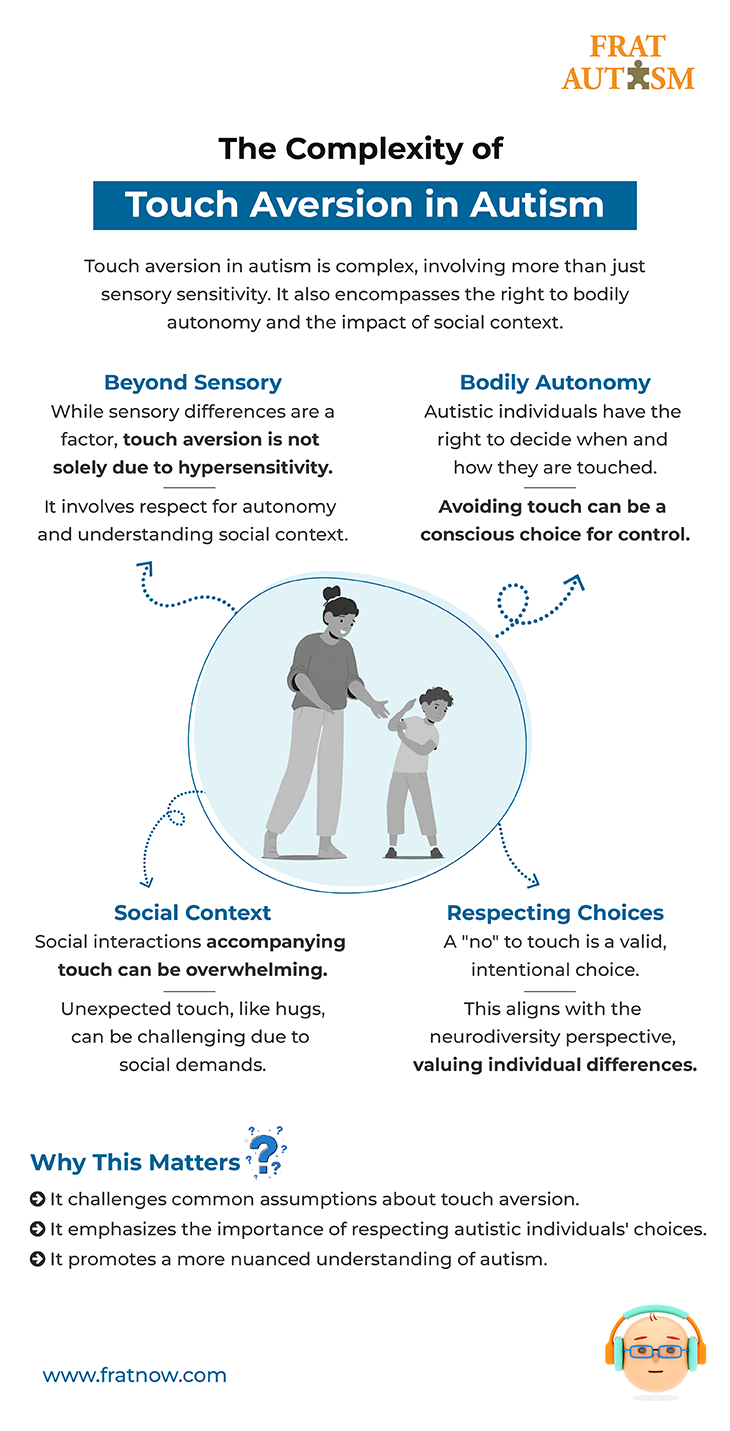

However, it’s crucial to understand that touch aversion in autism is not always solely about hypersensitivity. While sensory differences play a significant role, there’s a deeper layer to explore. It’s about autonomy, choice, and the social context surrounding touch. In this blog, we’ll delve into the complexities of touch aversion, moving beyond the common assumption that it’s simply a matter of sensory overload, and uncovering the importance of respecting individual boundaries and choices.

Signs of Touch Aversion in Autistic Children

Touch aversion can manifest in a variety of ways, and its expression may change as a child develops. It’s important to remember that not all autistic children experience touch aversion, and those who do will have individual triggers and sensitivities.

General Signs (Across All Ages)

- Withdrawal from Physical Affection

- Sign: Child pulls away, stiffens, or cries when hugged, kissed, or held.

- Example: A child flinches and pushes away when a parent tries to give them a comforting hug.

- Sensitivity to Clothing

- Sign: Child reacts negatively to certain fabrics, tags, or seams.

- Example: A child refuses to wear clothes made of wool or insists on wearing only soft, seamless clothing. Imagine wearing a sweater made of sandpaper—that’s the level of discomfort some clothing can cause.

- Discomfort with Textures

- Sign: Child avoids touching certain textures, like sand, play-doh, or lotion.

- Example: A child refuses to play in a sandbox or becomes distressed when their hands get sticky.

- Difficulty with Personal Care

- Sign: Child resists haircuts, nail trimming, or teeth brushing.

- Example: A child screams and struggles during haircuts or nail clipping because every hair being cut feels like a tiny, sharp tug.

- Avoidance of Physical Contact with Others

- Sign: Child avoids casual physical contact, like bumping into someone in a crowd.

- Example: A child becomes anxious in crowded spaces or avoids playing with other children who might accidentally touch them.

- Reactions to Light Touch

- Sign: Child reacts strongly to light, unexpected touch.

- Example: a child reacts negatively to the feeling of a light breeze, or when a very light touch brushes their skin.

- Food Textures

- Sign: Child has very specific food texture aversions.

- Example: A child will not eat mashed potatoes, or any food that has a slimy texture.

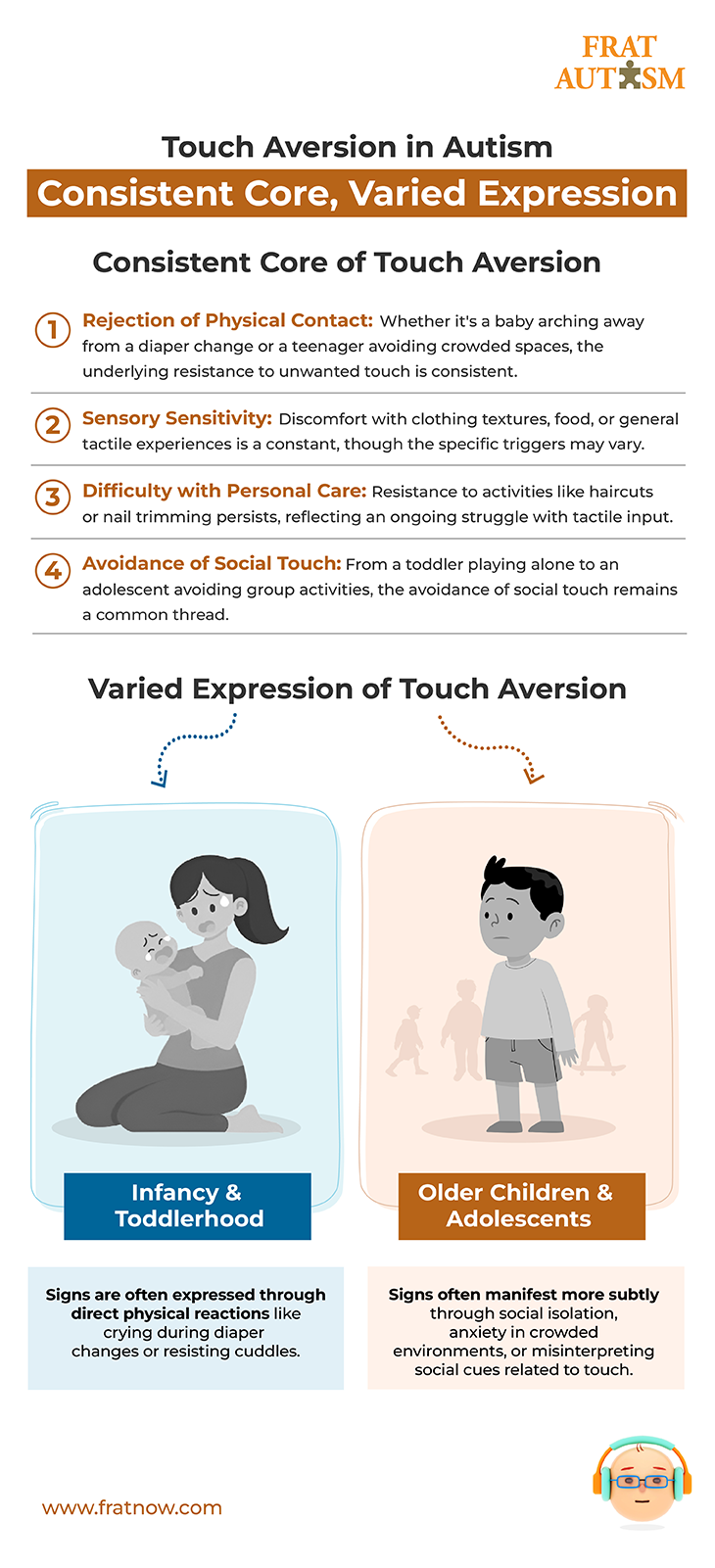

Signs in Younger Children (Infancy and Toddlerhood)

- Increased Irritability During Diaper Changes or Baths

- Sign: Child cries or becomes agitated during routine care.

- Example: A baby screams and arches their back during diaper changes or bath time.

- Resistance to Being Held or Cuddled:

- Sign: Child stiffens or pushes away when held.

- Example: A toddler prefers to play alone and avoids physical contact with caregivers.

Signs in Older Children and Adolescents

- Social Isolation

- Sign: Child avoids social situations that involve physical contact.

- Example: An adolescent avoids participating in group activities or sports that involve close physical proximity

- Anxiety in Crowded Environments:

- Sign: Child becomes anxious or overwhelmed in crowded spaces.

- Example: A teenager avoids going to school events or shopping malls.

- Difficulty with Social Cues Related to Touch

- Sign: Child may misunderstand or misinterpret social cues related to touch, such as a friendly pat on the back.

- Example: A child might perceive a friendly touch as aggressive or intrusive.

Autistic children may exhibit touch aversion across all ages, but the way these signs present themselves evolves. The core of the aversion remains rooted in a heightened sensitivity and a need for bodily autonomy, but the expression of these needs shifts with development.

Download Download & share this infograph card in your network [Free Download]

The Neurological Basis of Touch Aversion in Autistic Children

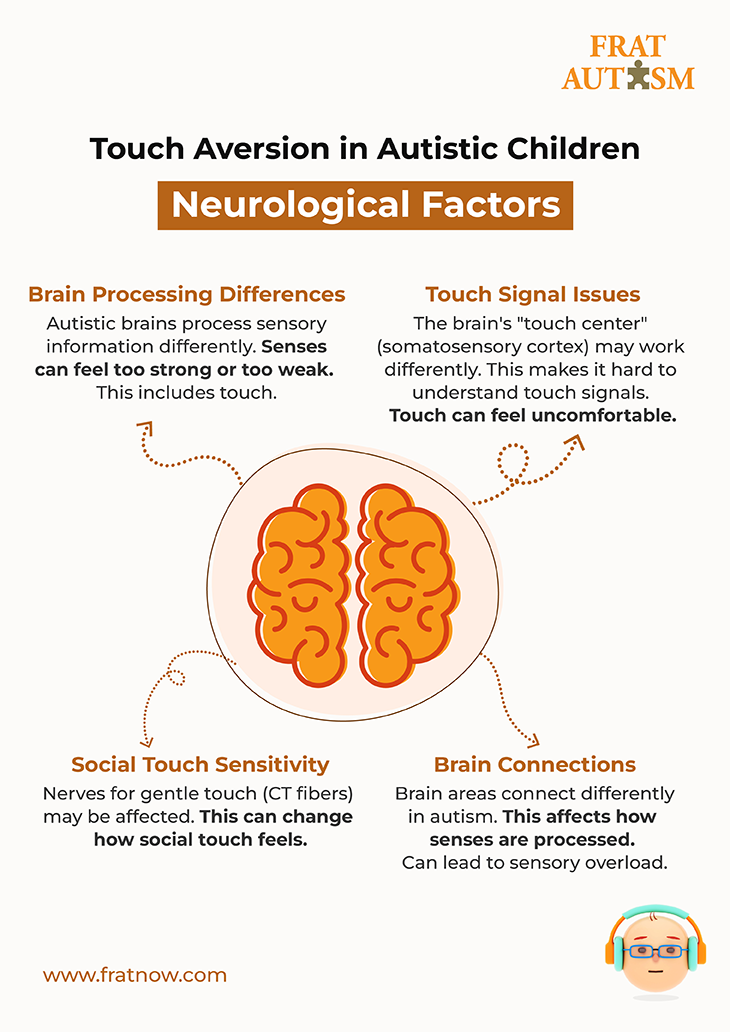

Touch aversion in autistic children is often rooted in differences in sensory processing within the nervous system. While the exact mechanisms are still being researched, several factors contribute to this phenomenon:

Altered Sensory Processing

- Autistic individuals often exhibit differences in how their brains process sensory information. This can lead to heightened sensitivity (hypersensitivity) or reduced sensitivity (hyposensitivity) to various stimuli, including touch.

- This altered processing can result in tactile input being perceived as more intense or overwhelming than in neurotypical individuals. The sensory information is not being filtered in the same way, thus causing sensory overload.

Dysregulation of the Somatosensory Cortex

- The somatosensory cortex is the part of the brain responsible for processing tactile information. Studies suggest that autistic individuals may have differences in the structure and function of this area.

- This dysregulation can lead to difficulties in accurately processing and interpreting tactile input, resulting in discomfort or distress. [2]

C-Tactile (CT) Afferent Fibers

- CT afferent fibers are specialized nerve fibers that respond to gentle, stroking touch, often associated with social touch. [3]

- Research indicates that some autistic individuals may have differences in the function or density of CT afferent fibers, which could contribute to atypical responses to social touch. [4]

- Studies have shown a reduction in the volume of these fibers in some autistic children.

Neural Connectivity Differences

- Autism is associated with differences in neural connectivity, meaning the way different brain regions communicate with each other. [5]

- These connectivity differences can affect the integration of sensory information, leading to sensory overload and heightened sensitivity.

- The brain regions that process social and emotional information have shown reduced responses to CT afferent stimulation in autistic people. [6]

Excitatory/ Inhibitory Imbalance

- The brain relies on a delicate balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission.

- Some researchers propose that autistic individuals may have an imbalance in this system, leading to increased neuronal excitability and heightened sensory responses. [7]

- This means that the brain is more reactive to incoming sensory information.

Neurodivergent Behavior and Sensory Avoidance

- These neurological differences can lead to behaviors aimed at regulating sensory input.

- Avoidance of touch is a common strategy for autistic children to minimize sensory overload and maintain a sense of control over their environment.

- The need for predictability and routine is often heightened in autistic individuals, and unexpected touch can disrupt this sense of stability, leading to anxiety and avoidance.

Download Download & share this infograph card in your network [Free Download]

Touch Aversion in Autism: More Than Just Sensory Overload

It’s a common assumption that touch aversion in autism is solely due to sensory hypersensitivity. While sensory differences undeniably play a role, recent research reveals a more nuanced picture. It’s not simply a matter of the physical sensation being overwhelming.

Autistic individuals, like everyone else, possess the fundamental right to bodily autonomy. This means they should have the freedom to decide when, where, and how they are touched. Sometimes, the avoidance of touch is a conscious assertion of this right, a way to maintain control over their own bodies and experiences.

Furthermore, the social context surrounding touch is crucial. It’s not always the tactile sensation itself that’s problematic, but the social interaction that accompanies it. For example, an unexpected hug might be overwhelming not just because of the physical contact, but because of the sudden social demand it places on the individual.

Studies analyzing real-life interactions, particularly “cuddles,” have shown that autistic children can and do enjoy physical affection. However, they also demonstrate a clear ability to resist or avoid touch when it conflicts with their autonomy or disrupts their ongoing activities. This highlights their sophisticated understanding of social interactions and their capacity for making informed choices. To explore this topic further, read our blog on how autistic children experience social interactions.

Ultimately, respecting the autonomy of autistic individuals means acknowledging that a “no” to touch is a valid, intentional choice, not merely a reactive sensory response. This aligns with the neurodiversity perspective, which celebrates individual differences and emphasizes the importance of understanding autism through the lens of individual agency and choice. [1]

Download Download & share this infograph card in your network [Free Download]

Practical Tips: Helping Your Autistic Child with Touch Aversion

Dealing with touch aversion can be challenging, but here’s a breakdown of practical steps you can take:

Teach "Ask First"

- Encourage your child to use the phrase “ask first” or a similar phrase to remind others to request permission before touching them.

Social Situations: Prepare and Educate

- Role-Playing: Practice social situations that might involve physical contact, like greeting friends or family.

- Educate Others: Explain your child’s sensory sensitivities to teachers, friends, and family. Provide them with practical tips for interacting with your child.

- Use Visual Communication Tools: In public spaces, consider using visual communication tools, such as pre-made cards or small signs, to discreetly communicate your child’s need for space. These cards could say something like, “I need some space today,” or “Please don’t touch me.” This allows your child to communicate their needs without drawing undue attention or feeling pressured to explain themselves verbally in potentially overwhelming situations.

Conclusion

Understanding touch aversion in autistic children requires us to move beyond simplistic explanations of sensory overload. While heightened sensitivity is a significant factor, it’s equally vital to recognize the importance of autonomy, choice, and the social context surrounding touch. As we’ve explored, touch aversion manifests in various ways across different ages, reflecting both neurological differences and a child’s need to control their own bodily experiences. This deeper understanding of touch aversion not only supports autistic children but also enriches our understanding of the diverse ways in which individuals experience and interact with the world around them.

References

- Disability Studies Quarterly, Autism, Autonomy, and Touch Avoidance

- PubMed Central, Somatosensory cortex functional connectivity abnormalities in autism show opposite trends, depending on direction and spatial scale

- PubMed Central, Pleasant Deep Pressure: Expanding the Social Touch Hypothesis

- PubMed Central, Atypical Response to Affective Touch in Children with Autism: Multi-Parametric Exploration of the Autonomic System

- PubMed Central, Brain Connectivity in Autism Spectrum Disorder

- PubMed Central, Brain Mechanisms for Processing Affective (and Nonaffective) Touch Are Atypical in Autism

- UC Davis Health, UC Davis developing models to predict the excitability of brain neuronal circuits

- Autism Research Institute, Sensory Integration in Autism Spectrum Disorders