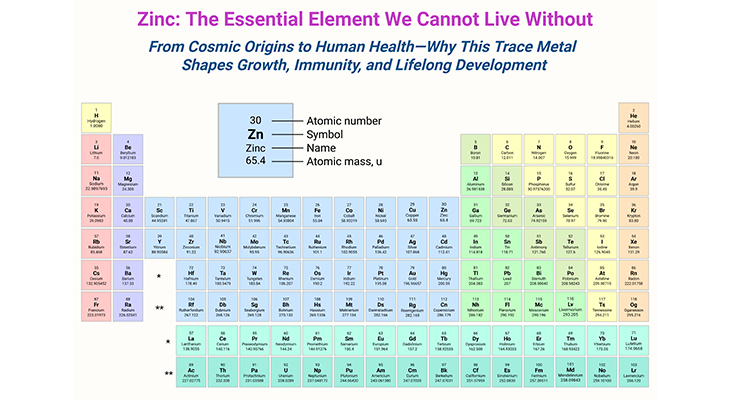

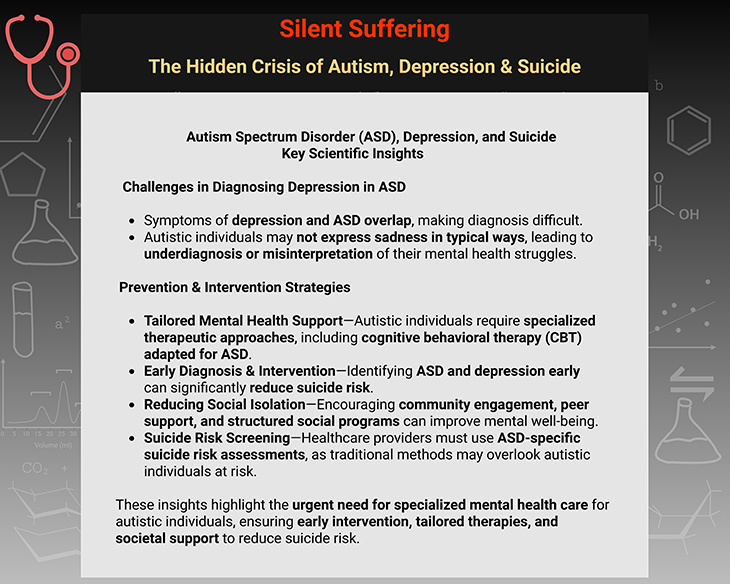

Figure 1. Suicide & Depression : The Silent Epidemic We Must Confront. (1) Suicide and depression are urgent public health crises, affecting millions worldwide. Despite growing awareness, stigma, misinformation, and systemic gaps in care continue to leave vulnerable individuals without the support they need. Suicide is not just a mental health issue—it is deeply intertwined with social, economic, and historical forces. From Durkheim’s sociological insights to modern research linking economic downturns to rising suicide rates, the evidence is clear: social isolation, financial hardship, and lack of access to care all contribute to this crisis. (2) One particularly overlooked group in suicide prevention is individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). A 2024 systematic review found that autistic individuals have an up to eightfold increased risk of death by suicide compared to non-autistic individuals. A 2021 study in JAMA Network Open reported that autistic individuals are three times more likely to attempt or die by suicide, with autistic women facing an even higher risk. Additionally, a 2023 meta-analysis revealed that 34.2% of autistic individuals experience suicidal ideation, and 24.3% have attempted suicide, highlighting the urgent need for tailored mental health interventions. (3) Many autistic individuals struggle with cognitive inflexibility, making it harder to see alternatives to suicide during emotional distress. Additionally, masking autistic traits to fit societal expectations can lead to mental exhaustion and increased suicidality. Late or missed diagnoses further exacerbate depression and suicidal ideation, leaving many without the support they need. (4) Yet, suicide is preventable. By breaking stigma, improving access to mental health care, and implementing evidence-based prevention strategies, we can save lives. This article explores the science, societal influences, and actionable solutions that can help us confront this silent epidemic—because no one should have to suffer in isolation. [For more information: https://www.cdc.gov/suicide/facts/data.html].

Introduction

The Silent Crisis: Understanding Depression and Suicide

In the shadows of modern society, depression and suicide remain among the most urgent yet misunderstood public health crises. Despite advances in mental health awareness, the stigma surrounding depression continues to silence countless individuals who struggle with its debilitating effects. Suicide, often the tragic consequence of untreated or severe depression, has reached alarming levels worldwide, with the United States witnessing a troubling resurgence in suicide rates.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), over 49,000 people died by suicide in 2023, marking one death every 11 minutes. Suicide is now the eleventh leading cause of death in the U.S., disproportionately affecting young adults (ages 10-34) and older individuals (85+). The crisis has deepened over the past two decades, with suicide rates rising by 37% between 2000 and 2018, briefly declining, and then returning to peak levels in 2022.

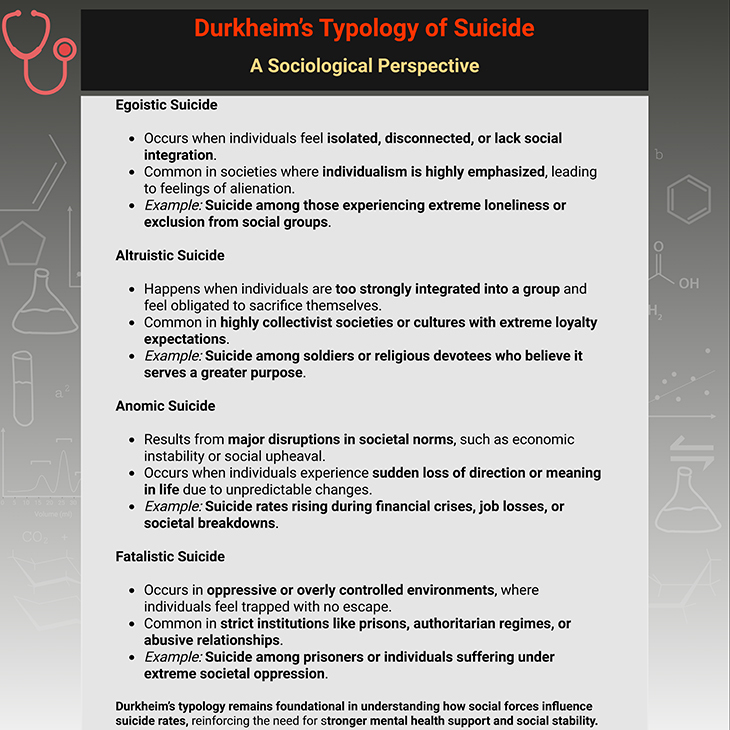

Beyond individual mental health struggles, social and economic forces play an equally significant role in shaping suicide trends. In 1897, French sociologist Émile Durkheim proposed a groundbreaking theory, arguing that suicide is not merely a personal decision but is strongly influenced by societal integration and economic stability. He observed that suicide rates fluctuate with major societal changes—lower during wartime when people feel unified by a common cause, and higher during economic crises when financial hardship increases stress, isolation, and desperation. Recent studies reinforce these connections, showing that economic downturns such as the 2008 financial crisis contributed to an estimated 10,000 excess suicides across Europe (see Figure 1) [1].

This complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors makes suicide prevention a multifaceted challenge. Economic downturns, social isolation, and untreated mental health conditions contribute to rising suicide rates, with firearms accounting for over 50% of suicides in the U.S. Additionally, middle-aged adults (35-54) and marginalized communities, including American Indian and Alaska Native populations, experience disproportionately high suicide rates, highlighting systemic gaps in mental health care.

Beyond statistics, the human cost of suicide is immeasurable—each life lost leaves behind grieving families, unanswered questions, and a ripple effect of emotional devastation. While depression is often treatable, barriers to mental health care, societal stigma, and lack of timely intervention prevent many from seeking help. Understanding the root causes, risk factors, and effective prevention strategies is essential in breaking the cycle of despair and fostering a society where mental health is prioritized, not ignored.

This article delves into the science, societal influences, and prevention strategies surrounding suicide, offering insights into how communities, policymakers, and individuals can work together to reduce suicide rates and support those in crisis.

Understanding Suicide: Causes, Trends, and Prevention Strategies

The Complexity of Suicide and Mental Health: Suicide is an immensely complex and deeply personal issue, often intertwined with mood disorders like depression and bipolar disorder. Individuals struggling with these conditions face a significantly higher risk, with research indicating that suicide rates among those with depression are 15 to 20 times higher than the general population. While a thorough exploration of the underlying causes, clinical assessments, and management strategies requires extensive analysis, this discussion provides an overview of suicide trends, societal factors, controversies, and effective prevention measures (see Box-1a and 1b).

Challenges in Reporting and Cultural Influences: One of the long-standing challenges in understanding suicide is the underreporting of cases due to cultural and religious taboos. In many societies, suicide has historically been labeled as sinful or illegal, leading to hesitation among coroners and public officials to classify suspicious deaths as suicide. This not only skews statistical accuracy but also perpetuates stigma, adding further distress for surviving family members. While attitudes toward suicide are evolving, ongoing debates—such as assisted dying for terminal patients and the right to die—highlight its ethical and social complexity.

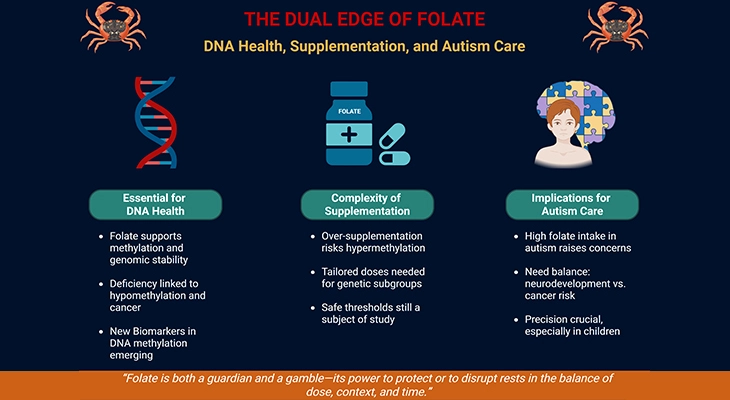

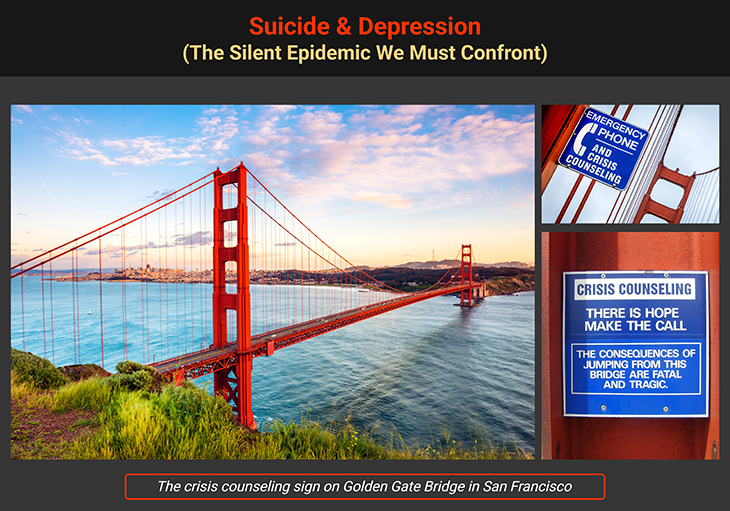

Box-1a. Silent Suffering: The Hidden Crisis of Autism, Depression & Suicide. (See below: Box-1b Cont.) [4-6]

Box-1b. Silent Suffering: The Hidden Crisis of Autism, Depression & Suicide. [4-6]

Suicide Statistics: Global Trends and Differences: According to the World Health Organization (WHO), one person dies by suicide every minute, equating to an annual toll of nearly one million lives worldwide. However, rates vary significantly across regions. Countries with strong religious and familial structures, such as Muslim and Latin American nations, report lower suicide rates (6 per 100,000 people), whereas countries in Eastern Europe—with historically higher social and economic stressors—report much higher rates (up to 30 per 100,000). Additionally, men are statistically more likely to die by suicide than women, often employing violent methods such as hanging or firearms, while women tend to opt for medication overdoses.

Age, Economic Influence, and Social Pressures: Suicide risk is not uniform across all age groups—the two highest-risk demographics are young adults (15-24 years old) and seniors over 65. In Western countries, suicide rates among young men have increased significantly, often linked to factors such as economic struggles, unemployment, alcohol abuse, and limited access to mental health support. Research suggests that economic downturns and recessions correlate with spikes in suicide rates-most notably, a study reported 10,000 excess suicides across Europe following the most recent financial crisis.

Box-2. Durkheim’s Typology of Suicide: A Sociological Perspective.

Durkheim’s Perspective: The Role of Social Integration: In 1897, French sociologist Émile Durkheim offered a groundbreaking perspective on suicide, arguing that social forces—not just individual psychology—play a critical role in suicide rates. His analysis revealed that suicide was less frequent during wartime and more common during economic depressions, emphasizing the importance of social connection and integration. His work paved the way for modern theories on how community involvement, access to mental health resources, and economic stability influence suicide prevention strategies (see Box-2) [1].

Addressing Depression and Suicide Prevention: Although depression increases suicide risk, most individuals recover through timely mental health interventions. Clinical programs now focus on early detection, timely treatment, and targeted support for vulnerable groups, particularly individuals recently discharged from psychiatric care. Importantly, asking patients about suicidal thoughts does not increase their risk of acting on them—instead, open conversations with professionals often provide immense relief (see Figure 2; Box-1a; and Box-1b) [2-3, 7].

Figure 2. Addressing Suicide as a Public Health Priority. Key Takeaways for Suicide Prevention: (1) Early detection and intervention are crucial—suicide risk screening must be continuous and adaptive, rather than relying on single assessments. (2) Reducing access to lethal means remains one of the most effective strategies for lowering suicide rates. (3) Community-based support systems, including helplines, peer networks, and responsible media reporting, play a vital role in suicide prevention. (4) Holistic treatment approaches, combining medication, therapy, and social support, improve outcomes for individuals with depression and suicidal ideation. (5) Addressing economic and social disparities can significantly reduce suicide rates, reinforcing the need for policy-driven mental health initiatives.

Media Influence and Copycat Suicides: The role of media coverage in suicide rates is widely debated. While direct evidence of copycat suicides remains inconclusive, publicized suicides of high-profile individuals have been linked to increases in deaths, sparking concerns about responsible reporting. Historically, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s 1774 novel, The Sorrows of Young Werther, led to a wave of suicides, prompting bans in several countries. In modern times, cyberbullying and online harassment have raised alarm over their potential contributions to suicidal ideation among youth, prompting efforts to regulate harmful online content.

The Most Effective Suicide Prevention Strategies: Among the most successful interventions are those that reduce access to lethal means. Countries with stricter firearm regulations tend to report lower suicide rates. Similarly, historical shifts—such as converting coal gas ovens to North Sea gas in the UK—have resulted in significant declines in suicide by gas poisoning (see Figure 1; Figure 2; Box-1a; and Box-1b).

Further preventative measures include:

- Restricting barbiturates (leading to a 23% decrease in suicides using these drugs).

- Blister packaging painkillers (slowing ingestion rates in overdose attempts).

- Installing barriers and nets on suicide hotspots (e.g., Clifton Suspension Bridge, Golden Gate Bridge) [see Figure 1].

- Expanding telephone helplines, such as The Samaritans, to provide confidential suicide prevention support.

Suicide Prevention as a Public Health Priority: Suicide prevention must be holistic, evidence-driven, and socially responsive. While individual treatment remains essential, broader societal interventions—including reducing access to means, responsible media coverage, and improved mental health accessibility—have the greatest impact in lowering suicide rates. By addressing economic pressures, social isolation, and stigma, societies can take meaningful steps toward safeguarding lives and fostering mental well-being [7].

This article serves as a broad introduction to the complex and multifaceted issue of depression and suicide, laying the foundation for deeper explorations in upcoming discussions. Future articles will build upon this groundwork, delving into Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), depression, suicide, and other comorbid mental health conditions, highlighting the unique challenges autistic individuals face in mental health care. Through scientific insights, risk factors, and targeted intervention strategies, we will expand our understanding of how neurodivergence intersects with psychiatric health, ensuring a comprehensive perspective on mental well-being and suicide prevention [4-6].

Take-Home Message

Strengthening Suicide Prevention Through Awareness & Action

- Suicide is a complex societal issue—it is influenced by psychological, economic, and social factors, not just individual mental health struggles.

- Depression significantly increases risk, but most individuals recover with timely intervention, structured support, and access to effective treatments.

- Historical and sociological insights, such as Durkheim’s theory, demonstrate that social connection and economic stability play crucial roles in suicide prevention.

- Economic hardship and social isolation contribute to rising suicide rates, with studies linking major recessions to surges in suicide cases worldwide.

- Men are statistically more likely to die by suicide, often using high-lethality methods such as firearms or hanging, while women tend to attempt suicide via overdoses.

- The media’s role in suicide coverage is significant-high-profile suicides and irresponsible reporting may contribute to copycat suicides, raising ethical concerns.

Final Thought: Mental Health is a Shared Responsibility

Suicide prevention is not solely the work of clinicians—it requires collective effort from policymakers, communities, educators, and individuals. By addressing mental health accessibility, economic disparities, and social isolation, we can build a world where those in crisis receive help before it’s too late.

(Cf. previous blogs entitled as: “Breaking the Chains of Depression: How Exercise Transforms Minds and Reclaims Lives.”; “Decoding Depression: Comprehensive Insights and Future Horizons.”)

Summary and Conclusions

Suicide remains a multifaceted crisis, shaped by biological, psychological, and societal influences. While depression and bipolar disorder significantly increase suicide risk, broader factors—including economic instability, social isolation, and media influence—also contribute to rising suicide rates. Historical perspectives, such as Durkheim’s sociological insights, reinforce the importance of social integration and economic stability in suicide prevention.

Recent research highlights critical gaps in mental health care, particularly in suicide risk screening and intervention strategies. A systematic review by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) emphasizes the need for improved screening tools to identify individuals at risk. Additionally, studies indicate that suicidal behavior fluctuates, making single-point assessments unreliable—clinicians must instead track patterns over time.

A retrospective study on suicide during depression further underscores the complex treatment challenges faced by individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD). Findings reveal that patients with suicidal ideation often require multimodal treatment approaches, including antidepressants, mood stabilizers, and electroconvulsive therapy, to reduce relapse rates.

Ultimately, suicide prevention requires a collective effort—from healthcare providers, policymakers, and communities—to ensure that individuals in crisis receive timely, effective support. By breaking stigma, improving access to care, and fostering social resilience, we can create a world where mental health is prioritized, and lives are saved.

For information on autism monitoring, screening and testing please read our blog.

References

- Durkheim, Émile. (1897). Le Suicide: Étude de sociologie. Paris: Alcan; Durkheim, Émile. (1951). Suicide: A Study in Sociology. Translated by John A. Spaulding & George Simpson. New York: The Free Press. (The foundational literature for Durkheim’s typology of suicide is his seminal work: This book remains a cornerstone of sociological inquiry, providing a systematic analysis of suicide as a social phenomenon.)

https://www.academia.edu/5961757/Suicide_A_Study_in_Sociology?auto=download

https://www.gacbe.ac.in/images/E%20books/Durkheim%20-%20Suicide%20-%20A%20study%20in%20sociology.pdf - Wang H, Lyu N, Huang J, Fu B, Shang L, Yang F, Zhao Q, Wang G. Real-world evidence from a retrospective study on suicide during depression: clinical characteristics, treatment patterns and disease burden. BMC Psychiatry. 2024 Apr 19;24(1):300. doi: 10.1186/s12888-024-05726-y. PMID: 38641767; PMCID: PMC11031916.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38641767/ - O’Connor EA, Perdue LA, Coppola EL, Henninger ML, Thomas RG, Gaynes BN. Depression and Suicide Risk Screening: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2023 Jun 20;329(23):2068-2085. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.7787. PMID: 37338873.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37338873/ - Takara K, Kondo T. Comorbid atypical autistic traits as a potential risk factor for suicide attempts among adult depressed patients: a case-control study. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2014 Oct 16;13(1):33. doi: 10.1186/s12991-014-0033-z. PMID: 25328535; PMCID: PMC4201698.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25328535/ - Brown, C.M., Newell, V., Sahin, E. et al. Updated Systematic Review of Suicide in Autism: 2018–2024. Curr Dev Disord Rep 11, 225–256 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-024-00308-9

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40474-024-00308-9 - Newell V, Phillips L, Jones C, Townsend E, Richards C, Cassidy S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of suicidality in autistic and possibly autistic people without co-occurring intellectual disability. Mol Autism. 2023 Mar 15;14(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13229-023-00544-7. PMID: 36922899; PMCID: PMC10018918.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36922899/ - Scott, Ann & Guo, Bing. (2012). For which strategies of suicide prevention is there evidence of effectiveness?. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/364521

HEN synthesis report: For which strategies of suicide prevention is there evidence of effectiveness?