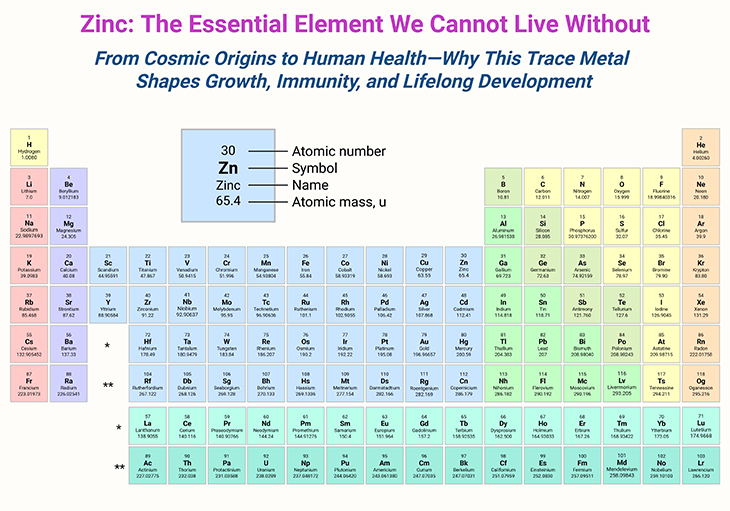

Figure 1. Zinc: The Essential Element We Cannot Live Without. From cosmic origins to human health – why this trace metal shapes growth, immunity, and lifelong development. [Adapted and modified from: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/periodic-table/]

Table of Contents

- Zinc — The Hidden Thread That Holds Life Together

- Zinc: The Quiet Architect of Life

- Zinc in Molecular Machinery

- When Zinc Becomes Hazardous

- Zinc in Food and Global Nutrition

- Zinc as a Remedy—Promise and Limitations

- Zinc in the history of medicine

- Self-medication, safety, and changing formulations

- From sunblock to nanoparticles

- Recognizing human zinc deficiency

- Zinc, alcohol metabolism, and liver health

- Take-Home Messages

- Summary and Conclusions

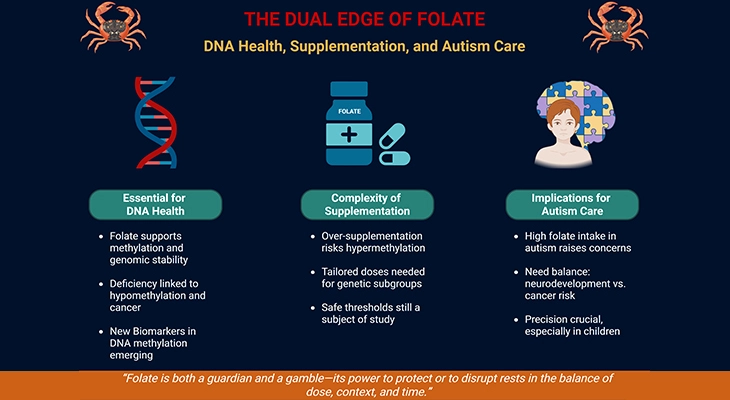

- Did You Know About Folate Receptor Autoantibodies (FRAAs) and Brain Development?

- References

Zinc — The Hidden Thread That Holds Life Together

Most people move through life without ever thinking about zinc. It is not as glamorous as gold, as familiar as iron, or as feared as lead. Yet this quiet, silvery metal—pronounced “zink” and named from the German zinke—is one of the most indispensable elements in the human story, woven into our biology from the first spark of life to the final breath.

Its importance became dramatically clear in 1968, when a young physician-scientist, Ananda Prasad, encountered a puzzling group of teenage boys in rural Iran. They were severely stunted, with delayed sexual development, profound fatigue, and chronic infections. Their symptoms resembled nutritional deprivation, yet their diets appeared adequate. Prasad recognized something no one had seen before: the first documented cases of human zinc deficiency. When he administered simple zinc sulfate supplements, the boys began to grow—sometimes several inches within months—and their health transformed. What had once been a medical mystery became a landmark discovery, revealing zinc as a critical determinant of human growth, immunity, and development [1-6].

Zinc’s medical significance did not end there. A rare genetic disorder, acrodermatitis enteropathica, once considered uniformly fatal in infants, was later traced to an inability to absorb zinc. What had been a death sentence became a fully treatable condition, with lifelong zinc supplementation restoring normal growth, immunity, and survival. These stories underscore a profound truth: life cannot proceed without zinc, and even small deficiencies can reshape the trajectory of human health.

Yet zinc’s influence extends far beyond these dramatic clinical tales. It is a cosmic element, forged in the explosive furnaces of supernovae and scattered unevenly across galaxies. It is a molecular architect, anchoring more than 200 enzymes and stabilizing the elegant “zinc-finger” motifs that allow transcription factors to read and regulate our DNA. It is a nutritional cornerstone, essential for taste, smell, cognition, fertility, wound healing, and immune defense. And it is a global public health concern, with an estimated 2 billion people consuming zinc-deficient diets—particularly those reliant on cereals, legumes, or tubers that block zinc absorption.

Despite its ubiquity, zinc is paradoxically fragile in human biology. The body stores little, loses about 1% of its total zinc each day, and depends heavily on dietary intake. Even in modern Western diets, zinc deficiency is more common than iron deficiency, especially among individuals with low meat consumption, chronic illness, or increased physiological demands such as pregnancy and lactation.

Zinc’s story is therefore not just chemical or biological—it is profoundly human. It is the story of how a seemingly modest element shapes growth, resilience, cognition, and survival. It is the story of how a deficiency, once overlooked, reshaped modern nutrition and medicine. And it is the story of how nature’s smallest building blocks can wield extraordinary power over the health of individuals and populations.

As we begin this chapter of Nature’s Building Blocks: Essential Human Elements, zinc invites us to look more closely at the quiet forces that sustain life—forces that are often invisible, yet utterly indispensable.

Zinc: The Quiet Architect of Life

Origins and Etymology

Pronounced “zink,” the element takes its name from the German zinke, possibly referring to its sharp, tooth-like crystals. Its linguistic trail may stretch even further back to the Persian sing, meaning stone, hinting at its ancient recognition as a distinct and useful metal (see Figure 1).

A Universal Essential

Zinc is indispensable to all known forms of life, from microbes to humans, and even plays a protective role in the industrial world—shielding steel from corrosion and preserving the elasticity of rubber. Its ubiquity in biology reflects its unique chemical stability as Zn²⁺, a non-toxic ion capable of binding to a wide array of molecules.

A Cosmic Rarity

Unlike lighter elements forged in ordinary stars, zinc nuclei are too large to form under typical stellar conditions. Instead, zinc is born in the cataclysmic furnaces of supernovae. Yet, paradoxically, the universe contains far less zinc than astrophysical models predict. Nearby galaxies appear to hold less than 20% of the expected amount.

A breakthrough came in 2006, when Varsha Kulkarni and colleagues, using the Very Large Telescope Interferometer on Mount Paranal in Chile, identified a Lyman-alpha galaxy 6.3 billion light-years away where the “missing” zinc appears to be concentrated—an intriguing clue to the metal’s cosmic distribution.

Element of Life

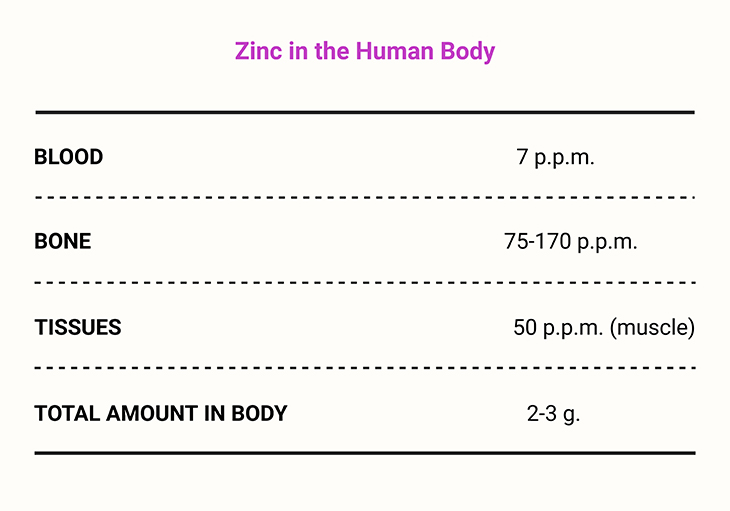

Zinc is generally regarded as non-toxic and is essential for animals, plants, and microorganisms. In plants, it contributes to drought tolerance and disease resistance. In humans, zinc accumulates most densely in the eye, prostate, muscle, kidney, and liver. Semen is particularly rich in zinc, and deficiency has been linked to reduced sperm counts [1-6] (see Table 1).

In the brain, zinc modulates neuronal activity, supports learning processes, and activates regions responsible for taste and smell—a reminder of its subtle but pervasive influence on sensory biology.

Table 1. Element of Life ~ Zinc in the human body.

Zinc in Molecular Machinery

Zinc is indispensable for two major classes of proteins:

- Enzymes

- Transcription factors

More than 200 zinc-dependent enzymes are known, and transcription factors containing zinc-finger motifs are similarly abundant. These proteins regulate growth, development, fertility, digestion, nucleic acid synthesis, and the immune response.

One of the most critical zinc enzymes is carbonic anhydrase, which enables the body to convert bicarbonate into carbon dioxide for exhalation. Zinc demand is especially high in tissues with rapid turnover—immune cells, bone marrow, and the intestinal lining.

Surplus zinc can be stored in the bones and spleen, though it is not easily mobilized during deficiency. The body loses about 1% of its total zinc daily, primarily through the intestines (90%), with smaller amounts lost via urine (5%) and sweat (5%) [1-6].

When Zinc Becomes Hazardous

Although biologically essential, zinc metal itself can irritate the skin, and inhaling hot zinc fumes can trigger metal fume fever, characterized by sore throat, cough, sweating, and, with heavy exposure, more severe symptoms.

Excessive dietary zinc can also be harmful, causing vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, and fever. Historically, mass poisonings have occurred when acidic fruit juices were stored in galvanized containers, leaching zinc into the liquid.

Zinc in Food and Global Nutrition

Zinc content in plants reflects soil levels. In zinc-rich soils, wheat contains 2–60 ppm, sweet corn about 20 ppm, and lettuce around 12 ppm. Fruits are poor sources, with apples and oranges containing ≤1 ppm (fresh weight).

Globally, zinc deficiency is widespread. The World Health Organization estimates that 2 billion people consume zinc-deficient diets, and nearly half the world’s population is at risk. Diets dominated by cereals and legumes are particularly vulnerable because phytic acid binds zinc into insoluble, non-absorbable zinc phytate. Populations relying heavily on tubers such as cassava or potatoes also face risk due to their naturally low zinc content [1-6].

To address this, several countries—including Mexico, Indonesia, and Peru—fortify staple foods with zinc.

Even in Western diets, zinc deficiency is more common than iron deficiency. Red meat is the richest source. Adults typically consume 5–40 mg/day, depending on meat intake. The minimum intake to avoid deficiency is 2–3 mg/day, but with an absorption rate of roughly 30%, recommended intakes are 7.5 mg/day for men and 5.5 mg/day for women. Average intakes—10 mg for men and 8 mg for women—are generally adequate.

During pregnancy and lactation, absorption efficiency increases. A breastfeeding mother produces about 850 cc of milk per day, containing ~2 mg of zinc for her infant. Cow’s milk used in formula must be fortified to match this requirement.

Zinc-rich foods include:

- Oysters: >7 mg/100 g

- Liver: 6 mg

- Beef: 4 mg

- Wheat: 4 mg

- Cheese: 3 mg

- Shrimp: 2 mg

- Eggs: 1 mg

- Milk: 0.4 mg

- Fruits average only 0.15 mg/100 g.

- Vegetarians can obtain zinc from sunflower and pumpkin seeds, brewer’s yeast, maple syrup, bran, and all nuts and seeds.

Zinc as a Remedy—Promise and Limitations

Zinc salts are widely sold in health stores and pharmacies and are often recommended for conditions such as anorexia nervosa, premenstrual tension, post-natal depression, acne, and the common cold. However, there is no robust scientific evidence that zinc supplementation reliably cures these conditions.

Zinc in the history of medicine

Although relatively few zinc-based medications are prescribed in modern clinical practice, zinc compounds once occupied a prominent place in the pharmacopeia. Over the centuries, physicians used zinc sulfate as an emetic, zinc chloride as an antiseptic, zinc oxide as an astringent to help stop bleeding, and zinc stearate as a base for ointments. The classic calamine lotion—a mixture of zinc and iron oxides—has been dispensed by pharmacies since the 1600s and remains a familiar treatment for minor skin irritations. Traditional zinc ointments, prepared by blending zinc oxide with plant oils, lanolin (wool fat), or mineral oil (liquid paraffin), were widely applied to eczema, nappy rash, scalds, and sunburn, reflecting zinc’s long-standing association with skin protection and repair.

Self-medication, safety, and changing formulations

Today, self-medication with zinc-containing remedies remains popular. Over-the-counter preparations are promoted for ailments such as the common cold, sore throat, and gastrointestinal upset. While some studies suggest that oral zinc lozenges may modestly shorten the duration of cold symptoms when taken early, the overall evidence remains inconsistent, and benefits are not guaranteed. A cautionary example comes from a zinc-containing nasal spray that was withdrawn from the market after it was found to damage the olfactory epithelium, leading to impaired or lost sense of smell.

Zinc continues to be a key ingredient in multivitamin formulations, reflecting its recognized essentiality, but its use as a targeted therapeutic agent is now approached with greater attention to dose, route of administration, and safety profile.

From sunblock to nanoparticles

In the 20th century, zinc oxide was widely used as a physical sunblock, providing effective protection against ultraviolet (UV) radiation that can induce skin cancer. It was commonly seen on the faces—especially the nose and lips—of outdoor sportsmen such as cricketers. However, its opaque white appearance limited its appeal for everyday cosmetic use. This aesthetic drawback paved the way for colorless nanoparticle formulations, particularly titanium dioxide (TiO₂) nanoparticles, which now dominate many modern sunscreen products. Interestingly, micronized and nanoparticulate zinc oxide has also re-emerged in contemporary sunscreens, offering broad-spectrum UV protection with improved cosmetic acceptability.

Recognizing human zinc deficiency

The importance of zinc for enzyme function was recognized early in the 20th century, but human zinc deficiency was not formally documented until 1968. In that year, Ananda Prasad, who had previously studied zinc deficiency in animals, identified similar features—stunted growth and delayed sexual maturation—in young men in Iran. His work established zinc deficiency as a clinical entity in humans.

Prasad later became a leading authority on human zinc deficiency, documenting numerous cases in Egypt, where zinc-poor soils contribute to low dietary intake. He demonstrated that zinc sulfate supplementation could effectively reverse deficiency symptoms, providing compelling evidence that zinc is not only essential but also therapeutically correctable when lacking in the diet [1-6].

Genetic disorders and life-saving zinc therapy

Zinc deficiency was also found to underlie the rare genetic disorder acrodermatitis enteropathica, a condition characterized by severe skin lesions, diarrhea, and failure to thrive. Once considered uniformly fatal in affected infants, it is now treatable and compatible with normal life through lifelong zinc supplementation. This transformation—from a previously lethal diagnosis to a manageable condition—stands as one of the most striking examples of zinc’s life-saving potential in clinical medicine.

Zinc, alcohol metabolism, and liver health

Zinc plays a crucial role in alcohol metabolism. The primary enzyme responsible for oxidizing ethanol in the liver, alcohol dehydrogenase, contains a zinc atom at its catalytic center, which is essential for its activity. Chronic excessive alcohol consumption damages the liver and has long been associated with reduced hepatic zinc levels, particularly in individuals with cirrhosis.

Clinical observations and interventional studies indicate that, when liver damage is not yet advanced, zinc supplementation can help restore enzyme function and support hepatic recovery, underscoring zinc’s importance not only in structural and regulatory biology but also in metabolic resilience.

Take-Home Messages

- Zinc is an essential, universal element—required by all living organisms and embedded in hundreds of enzymes and transcription factors that govern growth, immunity, metabolism, fertility, and sensory function.

- Its cosmic origins are extraordinary: zinc is forged in supernovae, and its uneven distribution across galaxies highlights both its rarity and its astrophysical significance.

- In humans, zinc is concentrated in high-demand tissues—the eye, prostate, muscle, liver, kidney, and brain—reflecting its central role in cellular turnover, neural signaling, and reproductive health.

- Zinc deficiency is far more common than widely recognized, affecting an estimated 2 billion people, especially populations dependent on cereals, legumes, or tubers that limit zinc absorption.

- Clinical zinc deficiency was first identified in 1968, transforming our understanding of stunted growth, delayed puberty, and immune dysfunction—and establishing zinc as a correctable global health issue.

- Zinc has a long medical history, from ancient ointments and calamine lotions to modern supplements, yet evidence for many popular zinc remedies remains inconsistent.

- Excess zinc can be harmful, causing gastrointestinal distress and, in rare cases, sensory damage—such as anosmia from intranasal zinc sprays.

- Zinc’s biochemical importance is profound: it anchors the catalytic core of enzymes like carbonic anhydrase and alcohol dehydrogenase, and its deficiency impairs liver function, immunity, and DNA repair.

- Genetic disorders such as acrodermatitis enteropathica, once fatal, are now fully treatable with lifelong zinc supplementation—an enduring testament to zinc’s therapeutic power.

- Dietary zinc varies widely, with red meat, shellfish, seeds, and whole grains providing the richest sources, while fruits and tubers contribute very little.

- Zinc homeostasis is delicate: the body stores it sparingly, loses ~1% per day, and relies heavily on dietary intake—making balanced nutrition essential across the lifespan.

(Cf. previous blogs entitled as: “Smart Starts: How Everyday Nutrients Shape Executive Function in Growing Minds.”; “The Brain on Food: Rethinking Mental Health from the Inside Out.”)

Summary and Conclusions

Zinc stands out as one of nature’s most indispensable building blocks—an essential trace element forged in supernovae yet deeply embedded in the biology of every living organism. Its influence spans enzyme catalysis, transcriptional regulation, immune defense, neurocognition, reproduction, wound healing, and the preservation of genomic stability. This breadth of function reflects zinc’s unique chemistry and its irreplaceable role in cellular life.

Clinically, zinc deficiency—first recognized in humans in 1968—remains a major global health challenge. Nearly 2 billion people are affected, particularly those dependent on cereal- or tuber-based diets that limit zinc absorption. The consequences range from impaired growth and delayed puberty to weakened immunity and increased susceptibility to infection. Zinc’s medical relevance extends further, from life-saving therapy for acrodermatitis enteropathica to its central role in alcohol metabolism, liver function, and the activity of more than 200 zinc-dependent enzymes.

Despite its ubiquity, zinc biology still contains important gaps. The precise molecular mechanisms by which zinc modulates neurotransmission, the long-term effects of marginal deficiency, and the interplay between zinc and the gut microbiome remain incompletely understood. The full regulatory landscape of zinc-finger transcription factors, which govern vast networks of gene expression, is still being mapped. Emerging evidence also points to zinc’s involvement in epigenetic regulation, cellular signaling, and age-related immune decline, but these areas require deeper investigation.

Another major challenge is the lack of precise biomarkers capable of distinguishing true zinc deficiency from functional insufficiency. Current clinical tests are limited, making it difficult to diagnose early deficiency or monitor response to supplementation. This gap underscores the need for more sensitive, specific, and globally accessible diagnostic tools.

Looking ahead, future directions include the development of biofortified crops, improved global supplementation strategies, and refined nanoparticle-based zinc formulations for medical and nutritional use. Personalized nutrition approaches—accounting for genetic variation, dietary patterns, and physiological states such as pregnancy, aging, and chronic disease—will be essential to optimize zinc intake across diverse populations.

Together, these insights highlight zinc’s broader importance as a foundational human element—one whose balance is vital not only for individual health but for global well-being. Its scientific story continues to unfold, offering profound implications for medicine, nutrition, and human development.

For information on autism monitoring, screening and testing please read our blog.

References

- Elgar, K. (2022) Zinc: a review of clinical use and efficacy. Nutr. Med. J., 1 (3): 46-69.

https://www.nmi.health/https://www.nmi.health/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/NMJ_Zinc_A-Review-of-Clinical-Use-and-Efficacy.pdf

(Comprehensive review covering zinc’s biochemical roles, deficiency patterns, clinical applications, and safety.) - Arribas Lopez E, Zand N, Ojo O, Kochhar T. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of zinc on wound healing. BMJ Nutr Prev Health. 2025 Feb 4;8(1):e000952. doi: 10.1136/bmjnph-2024-000952. PMID: 40771531; PMCID: PMC12322555.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40771531/

(Meta analysis showing zinc’s impact on ulcer healing (MD 1.41; 95% CI 1.04–1.92; p = 0.03).) - Prasad AS. Discovery of human zinc deficiency: its impact on human health and disease. Adv Nutr. 2013 Mar 1;4(2):176-90. doi: 10.3945/an.112.003210. PMID: 23493534; PMCID: PMC3649098.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23493534/

(Landmark review by the scientist who first identified human zinc deficiency; foundational for medical and historical context.) - King JC. Zinc: an essential but elusive nutrient. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 Aug;94(2):679S-84S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.005744. Epub 2011 Jun 29. PMID: 21715515; PMCID: PMC3142737.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21715515/

(Authoritative discussion of zinc absorption, biomarkers, and global deficiency challenges.) - Roohani N, Hurrell R, Kelishadi R, Schulin R. Zinc and its importance for human health: An integrative review. J Res Med Sci. 2013 Feb;18(2):144-57. PMID: 23914218; PMCID: PMC3724376.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23914218/

(Integrates biochemical, nutritional, and clinical perspectives on zinc’s essentiality.) - Maret W. Zinc in Cellular Regulation: The Nature and Significance of “Zinc Signals”. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Oct 31;18(11):2285. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112285. PMID: 29088067; PMCID: PMC5713255.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29088067/

(Explores zinc’s emerging role in cell signaling, neurobiology, and epigenetic regulation.)